NI Peace Heroines

Inez McCormack / Trade Unionist & Human Rights Activist

SR DR MAURA LYNCH / Medical missionary

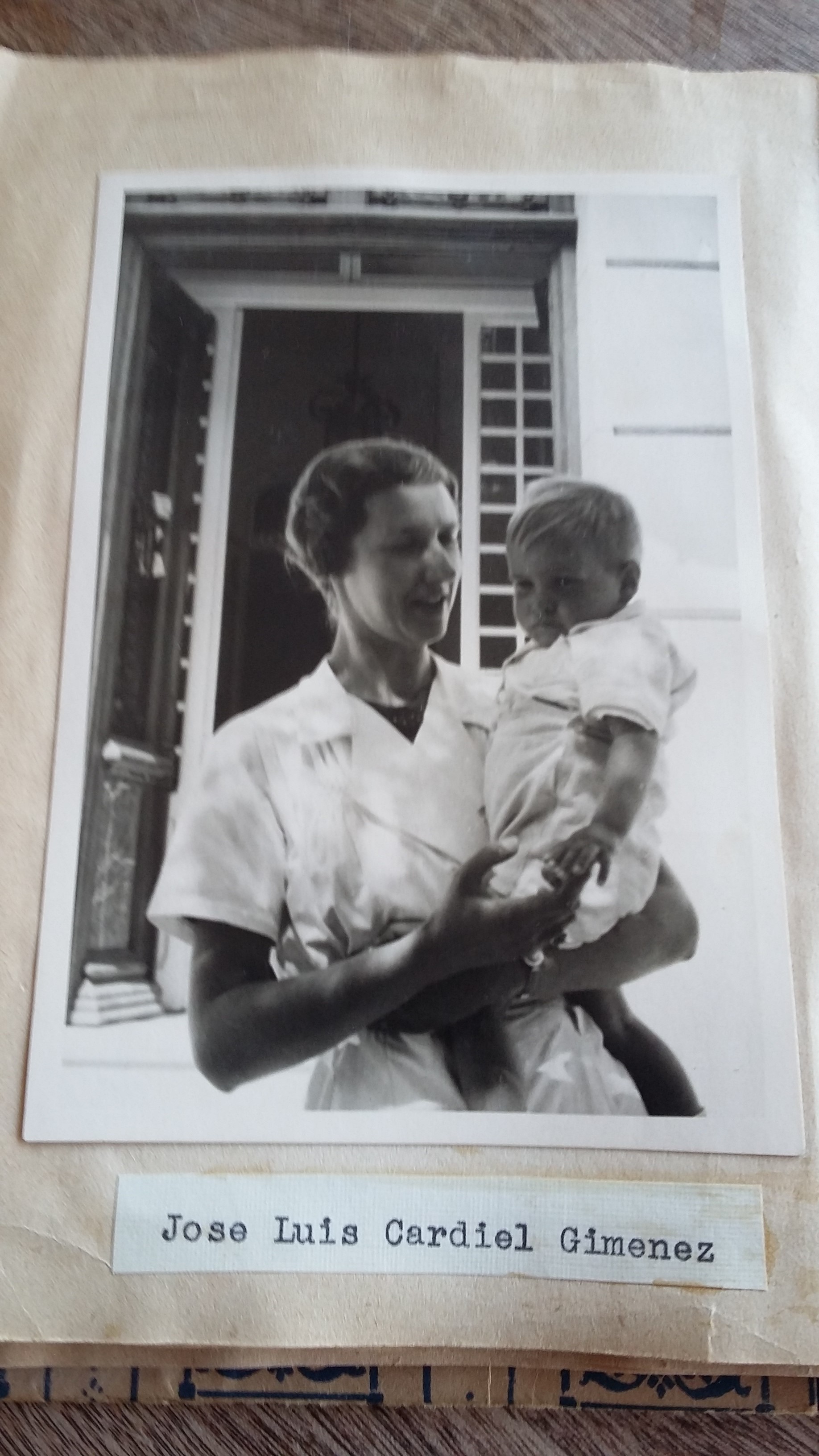

Image Source: Fistula Care Plus

Sr Dr Maura Lynch, 1938–2017

Medical missionary

In Uganda on 9 December 2017, a celebration was planned for the golden jubilee of the arrival in Africa of Youghal-born Sr Dr Maura Lynch, who devoted her life to improving the lives of African women. Sadly, she died suddenly in Kampala on that very day.

Maura was the fourth of the nine children of a teacher and a post office employee, and the family moved frequently. She joined the Medical Missionaries of Mary in Clonmel, Co. Tipperary at the age of 17. She studied medicine in UCD and came in the top three in her graduating class in 1965, and received a gold medal for surgery. She completed a Diploma in obstetrics and gynaecology at the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in London in 1966 and a Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Public Health in Lisbon in 1967. She would return to Dublin in 1985 to train as a surgeon.

Having completed her medical training, she left for Chiulo Mission Hospital in Angola, where she had to work across the range of medicine, surgery, obstetrics, gynaecology and paediatrics, and work as a lecturer and examiner in the Nurses Training School. She and only one other medical Sister had the care of 200 patients, many of whom suffered from TB, leprosy, or injuries sustained during the Angolan civil war. She and her colleagues risked their lives travelling the rough terrain of southern Angola by bicycle, sheltering in the undergrowth as aerial bombings pummelled the ground around them.

In 1987, she was assigned to Kitovu Mission Hospital in Uganda as a consultant surgeon, obstetrician and gynaecologist. There, she conducted her pioneering obstetric fistula repair work, performing over 1,000 procedures between 1993 and 2007. In the words of Professor Bill Powderly, former Dean of UCD School of Medicine, it is ‘an astonishing record that one can confidently say will never be bettered’.

Sr Dr Maura found her vocation in obstetrics, and developed a love of Uganda and its people. It must have been hugely gratifying to her, then, to receive a unique Certificate of Residency for Life from the Ugandan government in recognition of her work. She was a founding member of the Association of Surgeons of East Africa, and pioneered innovative training programmes in obstetric fistula repair. She fundraised for a centre of excellence in the treatment of obstetric fistula in St Joseph’s Hospital, Kitovu; it opened in April 2005.

Her accolades were many. In 2009, she was nominated by the United Nations Population Fund (Uganda) as a leader in the fight against fistula; in 2013, she received an Honorary Fellowship from the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; and in 2015, she was awarded the prestigious Council of Europe’s North–South Prize. She called for better education of girls and of medical staff to help the estimated 50–100,000 women affected annually by obstetric fistula, which is also linked to obstructed labour, reducing perinatal deaths. The 28-bed unit and dedicated operating theatre she established performs 250 operations per year; women are treated for free and, should they go on to become mothers, are offered free antenatal care and caesarean delivery.

Those who knew her spoke of her sense of fun, and her boundless energy; in 2013, she participated in a six-mile run to raise €5,000 for an overhead lamp for the operating theatre. Her position as a champion of African women’s healthcare is best expressed in the name given to her by her Ugandan patients: ‘Nakimuli’, meaning ‘Beautiful Flower’.

Sources: Joanna Lyall, ‘Maura Lynch: Fistula Fighter and Nun’, British Medical Journal, 360 (23 Mar. 2018); Irish Times, 23 Dec. 2017; ‘Sr. & Dr. Maura Lynch (1938–2017)’, https://digitalheritagecollections.rcsi.ie/rcsiwomen/sr-dr-maura-lynch-1938-2017/;‘Sr Dr Maura Lynch (1938–2017): Nakimuli–Beautiful Flower’, http://www.ucd.ie/medicine/ourcommunity/ouralumni/alumniprofilesinterviews/srdrmauralynch/.

Research by Dr Angela Byrne, DFAT Historian-in-Residence at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum. Featured in the exhibition 'Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women', a collaboration between Herstory, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

HARIOT GEORGINA HAMILTON-TEMPLE-BLACKWOOD, LADY DUFFERIN / Philanthropist, author, vicereine of India

Image Source: Virtual Museum of Canada

Hariot Georgina Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, Lady Dufferin, 1843–1936

Philanthropist, author, vicereine of India

Scattered around Myanmar, India and Pakistan stood a series of hospitals bearing the name of Lady Dufferin, an Anglo-Irish heiress who married, at the age of just 19, a man who became one of Britain’s most senior diplomats, governor-general in Canada, and viceroy in India. So much more than a diplomatic wife, Lady Dufferin left a particular legacy in India through her National Association for Supplying Female Medical Aid to the Women of India, better known as the Dufferin Fund.

The Dufferins arrived in India as viceroy and vicereine in December 1884, having previously lived in Canada and in St Petersburg, where they witnessed the anarchist terror campaign and the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. Dufferin quickly established a busy routine in India, taking lessons in Hindustani and in photography, and devoting much time to the establishment and running of her Fund. Her letters to her mother reveal her appreciation for the extent of the undertaking, and her trepidation on the occasion of the public launch: ‘I don’t in the least mind the work, but I sometimes shudder over the publicity and wish it were a quieter little affair.’ She gently but persistently pressed for funds at every opportunity, accepting donations from the Maharajas of Kashmir and Jeypore, holding a sports day and a Jubilee collection that elicited 400 pledges. The Fund doubtlessly saved lives and achieved its stated aim of alleviating the suffering of Indian women through childbirth and illness. However, it was not immune from criticism. Contemporary campaigners for equality for female doctors highlighted the Fund’s focus on zenana women to the detriment of non-zenana women, particularly lower-caste and working-class Indian women (who could not observe purdah due to the economic necessity of working outside the home).

Zenana women occupied the greater place in the minds of Victorian philanthropists and medical missionaries, who focused on the seclusion that denied them access to doctors and hospitals; Dufferin hospital boards debated issues like enclosing the buildings so that zenana women could move around freely inside without compromising their seclusion by being visible through a window, for example. Dufferin, during her time in India, remained assured of the necessity of the work by the testimony of Indian leaders who described to her the strict requirements of purdah: ‘in the harems in Scinde not even a man’s picture is admitted, much less a live doctor [...].’

She was disappointed when her husband was recalled to London, and described her tearful leave-taking on the steps of their residence. In 1907, its 23rd year, the Fund had 12 provincial branches, 140 local and district associations, and 260 hospital wards and dispensaries officered by women, who delivered care to over 2 million women and children. Working for the Fund were 48 ‘lady doctors with British qualifications,’ 90 assistant surgeons, and ‘311 hospital assistants with Indian qualifications.’ Subscriptions and donations in that year, to the UK branch alone, totalled over £4000. The Fund was very popular with colonial administrators, fundraised successfully in both India and the UK, and was popular among the Indian conservative elite.

Another important legacy of Dufferin’s initiative was its role in helping British and Irish women enter the medical profession. Zenana hospitals, for all their ethical problems, were in their early years an important source of employment for British women, who had few other opportunities to practice. The first woman to both train and qualify at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dr Mary Josephine Hannan, worked at the Dufferin Hospitals in Ulwar and Shikarpur in the 1890s.

Sources: Marchioness of Dufferin & Ava,Our Viceregal Life in India: Selections from my Journal( 2 vols, John Murray, 1889); ‘India’, British Medical Journal, 2, no. 2494 (29 Aug. 1908), 625; Samiksha Sehrawat, ‘Feminising Empire: the Association of Medical Women in India and the Campaign to Found a Women's Medical Service’,Social Scientist, 41,no. 5/6 (May–June 2013), 65–81 .

Research by Dr Angela Byrne, DFAT Historian-in-Residence at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum. Featured in the exhibition 'Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women', a collaboration between Herstory, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

ELIZABETH GURLY FLYNN / Activist, president of the American Communist Party

Image Source: ThoughtCo

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, 1890–1964

Activist, president of American Communist Party

While Mother Jones started her activist life approaching 60 years of age, Gurley Flynn started hers as a 16-year-old schoolgirl, calling on American workers to rise in front of a red flag on a makeshift stage on a New York street corner. Quickly becoming a ‘jawsmith’ (orator) for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), she was devoted to women, the working class, anti-racism, and anti-capitalism. Gurley Flynn was dedicated to women’s rights but saw feminism as bourgeois. She was a key figure in a generation of activists who saw class-based organization as key to the emancipation of women. She believed that women could never be free under capitalism; that only socialism could eradicate poverty and women’s economic dependence on men. She exemplifies intersectional feminism, recognising that the universal category of woman did not acknowledge the additional struggles faced by African American women, for example.

Gurley Flynn’s Irish parents were committed socialists and atheists, who imbued their children with a hatred of capitalism and empire. Annie Gurley encouraged her daughters to aspire to meaningful careers; she continued to work as a seamstress after marriage, at times supporting the household. While Gurley Flynn married at nineteen and had a son, this never defined her and she was determined to be financially self-sufficient (except during her ten-year relationship with the physician, Dr Marie Equi, when she rarely left their Portland home).

As a single parent, with the support of her mother and sister, she maintained her political commitments and gruelling schedule of US-wide public talks. When she started her career with the IWW (or ‘Wobblies’), workplace disputes commonly involved violence, long-drawn-out strikes, and lockouts. She was a brilliant strategist who pioneered new tactics, such as getting workers to sit idle at their machines, which eliminated ‘scab’ labour and prevented lockouts.

By 1910, she was the leading woman in the IWW. She also began to publicly advocate for women’s access to birth control, when it was still illegal to advertise such products in the press. In 1936, after a ten-year hiatus in Portland, Gurley Flynn returned to New York and joined the Communist Party, rising rapidly through its ranks. During the Cold War, communists were harassed and imprisoned as ‘un-American’. Gurley Flynn was one of over 100 communists imprisoned for their views in the 1950s, spending 28 months in the maximum-security wing of Alderson Female Penitentiary, West Virginia, in 1955–7. She had been in a similar position in 1917, when she and other members of the IWW were charged with ‘seditious conspiracy’, a charge next to treason.

American anti-communism only made Gurley Flynn more resolute in her commitment to freedom of speech and political association. She supported deportees who, under the 1918 Immigration Act, were summarily expelled as ‘alien anarchists’ without warning, and without their families. World War II gave American communists a brief reprieve, thanks to the alliance between the USA and the USSR. Gurley Flynn used this time to build a national platform and a wide support base, and to pursue feminist goals.

Her aims as director of the Women’s Commission of the Communist Party included the representation of women at all levels within the Party ‘against all concepts of male superiority’, and the full enfranchisement of African Americans and poorer women. Fascism, as she saw it, placed women in a subordinate position, so she framed gender equality as anti-fascist against the backdrop of millions of ‘Rosie the Riveters’ filling vacant jobs in factories. By 1943, 50% of the Party’s membership was female.

In 1961, she became the first woman elected head of the American Communist Party. She died on her second visit to Moscow in 1964. Lauded as a heroine in the USSR, she was given a full state funeral and Nina Khrushcheva was one of her pallbearers. Half of her ashes were buried by the Kremlin walls; the other half were conveyed to Chicago. Perhaps too-willing to believe that the ideals to which she had committed her life had been realised in the USSR, she never questioned Soviet propaganda about the quality of women’s lives under communism.

Sources: Lara Vapnek, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn: Modern American Revolutionary (Westview Press, 2015); Obituary, New York Times, 6 Sept. 1964.

Research by Dr Angela Byrne, DFAT Historian-in-Residence at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum. Featured in the exhibition 'Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women', a collaboration between Herstory, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

CYNTHIA LONGFIELD / Entomologist, world traveller

Cynthia Longfield, 1896–1991

Entomologist and world traveller

Cynthia Longfield, ‘Madam Dragonfly’, was born in London in 1896 to Anglo-Irish parents. The family divided their time between London and the ancestral home in Cloyne, Co. Cork, where she enjoyed roaming the countryside. Her early love of nature and insects grew into a lifelong passion, and she became a leading authority on dragonflies and damselflies. Longfield’s interest in the sciences was fostered in childhood, with her mother’s encouragement. She was inspired at an early age by reading about Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and his Beaglevoyage of 1831–6. She later wrote, ‘I went on the St George expedition to follow Darwin’s footsteps–and I got there!’ She absorbed the importance of fieldwork and travel, both of which played important roles in her life and in her scientific work.

It was in 1921, during her first overseas tour–taking in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Panama,Jamaica and Cuba–that her passion for entomology blossomed. In 1924, she participated in the St George scientific expedition, an 18-month-long re-enactment of Darwin’s Beaglevoyage, taking in Coiba, Cocos Island, the Galapogos, the Marquesas, the Tuamotu Archipelago and Tahiti. During the expedition, Longfield collected moths, beetles and butterflies for the Natural History Museum in London. Following this, she worked, unpaid, as a cataloguer at the museum, where she had responsibility for the dragonfly collection. Her personal circumstances freed her from the need for paid employment. She would remain in this post for 30 years, but continued to travel the world in search of specimens.

In 1927, she participated in a six-month-long scientific expedition in the Mato Grosso, Brazil, where she collected 38 species of dragonfly, three of which were new species. She went on to make scientific expeditions to south-east Asia in 1929, where she collected hundreds of moths and butterflies; to Kenya, Uganda, Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) and South Africa in 1934, where she travelled alone and identified six new species of butterfly and dragonfly; and to Cape Town and Zimbabwe in 1937.

She was forced to return to London when she contracted malaria in 1937, and was prevented from returning to Africa by the outbreak of World War II. During the war, she volunteered for the Auxiliary Fire Service in London. She had previously worked with the Royal Army Service Corps and in an aeroplane factory during World War I. Longfield did not limit herself to quietly cataloguing species in the museum. She regularly published her findings, sat on museum committees, and was a member of the Entomological Society, the Royal Geographical Society, and the London Natural History Society.

In 1937, she published the sell-out The Dragonflies of the British Isles, which became the standard handbook on the topic. She retired from London’s Natural History Museum in 1956 and returned to Cloyne, but never stopped travelling or studying entomology. Two dragonfly species were named in her honour: Corphaeschnalongfieldae (Brazil) and Agrionopter insignis cynthiae (Tanimbar Islands). She donated her personal archive and library, some 500 volumes, to the Royal Irish Academy in 1979, and her Irish specimen collection to the Natural History Museum in Dublin.

Sources:Jane Hayter-Hames,Madam Dragonfly: The Life and Times of Cynthia Longfield( Pentland Press, 1991);Dictionary of Irish Biography online edition; Royal Irish Academy Longfield Collection.

Research by Dr Angela Byrne, DFAT Historian-in-Residence at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum. Featured in the exhibition 'Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women', a collaboration between Herstory, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

MARY AGNES LEE / Women's suffrage campaigner

Mary Agnes Lee, 1821–1909

Women’s suffrage campaigner

Born in Co. Monaghan in February 1821, she is now remembered as one of the most prominent Australian suffragists, but she also advocated on behalf of women workers and asylum residents.Following the death of her church-organist husband, Lee and one of her daughters emigrated to Australia in 1879 to care for her terminally-ill son.After his death,Lee remained in Australia,because she could not afford to return to Ireland and had grown fond of ‘dear Adelaide’.

Freshly liberated from domestic obligations at almost 60 years of age, Lee threw herself into politics.She first became secretary to the Social Purity Society, lobbying for the Criminal Law Consolidation Amendment Act (1885) that raised the legal age of consent to sixteen.Historian Audrey Oldfield described how a‘large and enthusiastic’ public meeting convened to institute the South Australian Women’s Suffrage League on 21 July 1888, rejecting any limitation of age or property on women’s suffrage. Lee was elected co-secretary to the committee of 13 women and 15 men, quickly proving herself a fiery orator and becoming the best-known champion of South Australian women’s suffrage. Lee herself stated, ‘If I die before it is achieved, “Women’s enfranchisement” shall be found engraved upon my heart.’

Lee was a suffragist, meaning she preferred constitutional means to secure equality of franchise. She seems to have been less concerned about enabling women to run for elected office;she declined an invitation to run for election in 1895. Nevertheless, her emphasis on social justice and her concerns for working women posed a threat to the establishment. She supported the foundation of women’s trade unions, and was secretary to the newly-formed Working Women's Trades Union in 1891–3. She visited the clothing factories in which women workers ‘sweated’, convincing employers (with varying degrees of success) to set union wages. She also distributed food and clothing to the impoverished.Lee corresponded with New Zealand suffragists, who had achieved their aims in 1892. She organised a petition of 11,600 signatures from across the colony of South Australia in 1894. The 122-metre-long document was presented to the House of Assembly in August 1894, while women swamped MPs with telegrams, and filled the galleries of the House.In December 1894, South Australian women became the first in Australia to gain a parliamentary vote on the same terms as men. This was a landmark moment in international suffrage and was achieved with both middle-and working-class support. It is important to remember, however, that neither male nor female Indigenous Australians would have equality of franchise until the 1960s. In 1896, she became the first woman appointed as an official visitor to asylums, a role she conducted for twelve years with great compassion for the patients.

Lee’s activism was recognised in her lifetime. On her 75th birthday, Adelaide town hall presented her with 50 sovereigns from public donations; a public address praised her leading role in the suffrage campaign. However, her later years were marked by financial difficulties, and her pleas for further public aid fell on deaf ears, despite the great personal sacrifices she had made during decades of activism. One biographer suggests that her ‘sharp tongue and uncompromising attitude’ left her with few friends–evidence that, while women had secured voting rights, they were still expected to conform to certain behavioural norms.She died at her home in Adelaide in September 1909 and her tombstone bears the words: ‘Secretary of the Women's Suffrage League’. Its understatement forms a sharp contrast with the passionate campaigning that consumed the last 20 years of her life.

Sources:Australian Dictionary of Biography online edition; Audrey Oldfield,Woman Suffrage in Australia (Cambridge University Press, 1992);Dictionary of Irish Biography online edition; James Keating, ‘Piecing Together Suffrage Internationalism: Place, Space, and Connected Histories of Australasian Women’s Activism’,History Compass, 16, no. 8(2018).

Research by Dr Angela Byrne, DFAT Historian-in-Residence at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum. Featured in the exhibition 'Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women', a collaboration between Herstory, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

EVA GORE-BOOTH / Suffragist, Trade Unionist, Poet, Mystic

Eva Gore-Booth, 1870–1926

Suffragist, trade unionist, poet, mystic

Eva Gore-Booth led a rich and active life beyond what might have been expected of her–not because of her gender,or her aristocratic background, but because of her physical frailty and susceptibility to illness. She collected 30,000 signatures for a suffrage petition in 1901, campaigned for the rights of women to work as barmaids and acrobats, was a member of the executive committee of the North of England Society for Women's Suffrage, and was a vegetarian and animal rights advocate. She has long been overshadowed by her more famous sister, Constance Markievicz; even in childhood,her governess recalled, Eva was ‘always so delicate ... rather in the background’.

Eva met her lifelong partner, Esther Roper in 1896 in an Italian olive grove; wordlessly, a lifelong connection was made. Roper was a Manchester suffragist and trade unionist; inspired, Gore-Booth established the Sligo branch of the Irish Women’s Suffrage and Local Government Association. In 1897,Gore-Booth left Lissadell to join Roper in Manchester, where Constance Gore-Booth got her ‘first taste of political campaigning’ when she went to help Eva and Roper in Manchester in the 1908 by-election. She also helped with Eva’s campaign in support of barmaids. In the same year, Gore-Booth published her first book of poems. Gore-Booth and Roper were a team, both believing in the need to marry trade unionism and suffrage, not least because in Lancashire, cotton factory work–and therefore union membership–was dominated by women. They were joint secretaries of the Women’s Textile and Other Workers’Representation Committee, and jointly ran the The Women’s Labour News. Together, they campaigned for pit-brow workers, florists, and barmaids, bringing large numbers of working-class women into the suffrage movement–a radical, unprecedented move.

In 1914, Gore-Booth threw herself into pacifism and the Committee for the Abolition of Capital Punishment. Despite her enduring ill-health, she travelled all over Britain with the Women’s Peace Crusade and attended the courts-martial of conscientious objectors.Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington recalled how, in the aftermath of Easter 1916, Gore-Booth travelled to Dublin to plead for leniency for the Rising’s leaders.

The historian Sonja Tiernan has done much to restore the commitment of Roper and Gore-Booth’s partnership, in every respect, to the historical record. Roper and Gore-Booth’s loving written tributes to one another bear every mark of devotion and tenderness. Roper wrote that ‘Even simple everyday pleasures when shared with her became touched with magic’. Eva, for her part, dedicated her poem ‘The Travellers’ to Roper :‘You whose Love’s melody makes glad the gloom’. In addition to their tireless work for women’s suffrage and trade unionism, Gore-Booth and Roper publicised gay and trans issues. In 1916, together with trans woman Irene Clyde, they founded the periodical Urania, publishing articles on transvestitism and advocating for a genderless society. Gore-Booth died of cancer in January 1926, in the home that she and Roper shared. In a final testament to their partnership, they are buried in the same grave.

Sources:Poems of Eva Gore Booth, ed. Esther Roper (Longmans, Green and Co., 1929);Sonja Tiernan, ed.,The Political Writings of Eva Gore-Booth(Manchester University Press, 2015);Anne Marreco,The Rebel Countess([1967] Phoenix Press, 2000);Sonja Tiernan, ‘Challenging Presumptions of Heterosexuality: Eva Gore-Booth, A Biographical Case Study’,Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques, 37, issue 2 (2011); ‘LGBT History Month’,https://wearewarpandweft.wordpress.com/stature-project/lgbt-history-month/

Research by Dr Angela Byrne, DFAT Historian-in-Residence at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum. Featured in the exhibition 'Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women', a collaboration between Herstory, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

NELLIE MC CLUNG / Suffragist, writer

Nellie McClung, 1873–1951

Suffragist, writer

A girl raised in the wheat belt of frontier Manitoba became Canada’s leading suffragist, the first woman to sit in the Alberta legislature, and author of sixteen volumes of fiction and non-fiction. She remains controversial, but her role in the achievement of women’s suffrage in Canada is unquestionable.

She was born in Ontario in 1873, the youngest of seven children of Irish Methodist farmer John Mooney and Scottish Presbyterian Letitia McCurdy. From an early age, she was passionate about women’s rights, objecting to male privilege, domestic abuse, and alcohol. As a teacher, she became a leader in local affairs and a member of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the leading women’s organization of the day.

In 1896, she was obliged to retire from teaching when she married pharmacist and fellow WCTU member, Robert Wesley McClung. Robert shared Nellie’s views, but it was only thanks to hired domestic servants that she managed to juggle a busy activist life with domestic responsibilities and the care of four children; that help is acknowledged in her autobiography, The Stream Runs Fast (1945).

When the family moved to Winnipeg in 1911, Nellie found herself at the forefront of Manitoba’s suffrage and temperance movements. She founded the Political Equality League, ‘barnstormed’ Canada and the USA as one of the most popular suffrage speakers, and hosted British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst at her home in 1911.

In January 1914, McClung and other Winnipeg suffragists attracted much publicity by holding a ‘Women’s Parliament’ in a city theatre. Women held the seats, and men had to petition for the vote.

McClung played an important role in the achievement, in 1916, of provincial suffrage in Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan. It is important to note that when Ottawa completed the process of federal franchise in 1919, First Nations, Inuit and other ethnic minorities were excluded.

In 1921, McClung became the first woman MLA in Alberta, campaigning for a minimum wage for women, mothers’ pensions, and equality in divorce. However, she also supported the Alberta Sexual Sterilisation Act, that permitted the forced sterilisation of some 2,800 so-called ‘mental defectives’ up to 1972. First Nations and métis people, who made up a large proportion of the province’s population, suffered the greatest degree of harm under this law.

When McClung moved to Calgary in 1926, she lost her seat in the Alberta legislature. She remained active, however, and was part of a successful ten-year campaign for women to be recognised as ‘persons’ for the purpose of eligibility for the Canadian Senate. In 1936, she was appointed to the board of governors of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and in 1938, joined the Canadian delegation to the League of Nations.

McClung left a complex legacy. She did not tolerate fascism, National Socialism or xenophobia. This, and her lifelong support for women’s rights – including day-care, contraception, and equal wages – sits in sharp contrast to her willingness to overlook the rights of First Nations, Inuit, and métis women, and women with disabilities.

Sources: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition; Nellie L. McClung, In Times Like These, ed. Veronica Strong-Boag (University of Toronto Press, 1992); Nellie L. McClung, The Next of Kin (Thomas Allen, 1917); Joan Sangster, ‘Mobilising Women for War’, in Canada and the First World War, ed. David MacKenzie (University of Toronto Press, 2005), 157–93; Yvonne Boyer, ‘First Nations Women’s Contributions to Culture and Community through Canadian Law’ in Restoring the Balance, ed. Gail Guthrie Valaskakis, Madeleine Dion Stout and Eric Guimond (University of Manitoba Press), 69–96.

Research by Dr Angela Byrne, DFAT Historian-in-Residence at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum. Featured in the exhibition 'Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women', a collaboration between Herstory, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

ANNIE BESANT / Secularist, politician, theosophist

Annie Besant, 1847–1933

Secularist, politician, theosophist

Annie Wood was born in London in 1847 to Irish parents. At nineteen, she married, more out of duty than attraction, Reverend Frank Besant. He was seven years her senior, and she later admitted that they were ‘an ill-matched pair’. She took up writing in 1868 and was dismayed to learn that as a married woman, her earnings were not her own. The couple had two children in eighteen months, and the prospect of a third horrified Annie, not least for financial reasons.

Besant’s struggle with her faith began in 1871, when her daughter almost died of whooping cough. Discovering that she had turned to freethought, her husband gave her an ultimatum: take communion regularly in his parish, or leave. ‘Hypocrisy or expulsion,’ she later recalled – ‘I chose the latter.’ She obtained a legal separation and a small allowance, and moved to London with her daughter, becoming at first a women’s rights activist. ‘Red Annie’ was born.

From 1874, she became one of the National Secular Society’s most effective public speakers, filling halls across Britain. She also worked as a journalist for the National Reformer.

In March 1877, the Freethought Publishing Company was prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act for issuing a treatise on contraception. At the trial, Annie became the first woman to publicly endorse birth control; part of her argument was the alleviation of poverty. However, her estranged husband argued that this made her an unfit guardian, and reclaimed custody of their daughter, much to Annie’s distress.

By the late 1880s, Annie was a leading socialist: a member of the executive of the Fabian Society, editor and contributor for an array of socialist publications, and author of Why I am a Socialist and Modern Socialism. On ‘bloody Sunday’, 13 November 1887, she led a procession on Trafalgar Square by East End workers. In 1888, she was instrumental in the establishment of the Matchmakers’ Union, the first union to exclusively represent women workers. In 1889, she was elected to Tower Hamlets’ school board.

Suddenly, in 1889, she turned to theosophy, having been convinced by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Russian co-founder of the Theosophical Society. Her beliefs changed completely and she reversed her position on birth control. Like other Victorian converts, she may have been attracted by Theosophy’s female leadership and its rejection of Judaeo-Christian patriarchy.

In 1891, Blavatsky died, leaving Besant head of the Society. She arrived at their Madras headquarters on 16 November 1893. She dedicated herself to Indian education, founding, in 1897, the Central Hindu College in Benares. She adopted Indian dress, attempted to follow Indian social customs, and published her own translation of the Bhagavad Ghita from the original Sanskrit (1895).

From 1907, she was active in the campaign for Indian self-government. In 1913, she joined the Indian National Congress, becoming its first woman president in 1917. She was interned for her Indian nationalism in May–August 1917.

After 1917, her influence in Indian politics diminished, not least due to her opposition to Ghandian passive resistance. Her last official appointment was in 1928, as a member of the Nehru committee to draft an Indian constitution. In the 1920s, her position as president of the Theosophical Society took her all over the world. She died at Adyar on 20 September 1933 and was cremated there. On her death, many tributes were paid by Indian feminists.

Sources: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition; Annie Wood Besant, Annie Besant: An Autobiography (T. Fisher Unwin, 1893); Nancy Fix Anderson, ‘Bridging Cross-Cultural Feminisms: Annie Besant and Women’s Rights in England and India, 1874–1933’ in Women’s History Review, 3 (1994), 563–80; Louise Raw, Striking a Light: The Bryant and May Matchwomen and their Place in Labour History (Continuum, 2009).

Research by Dr Angela Byrne, DFAT Historian-in-Residence at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum. Featured in the exhibition 'Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women', a collaboration between Herstory, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

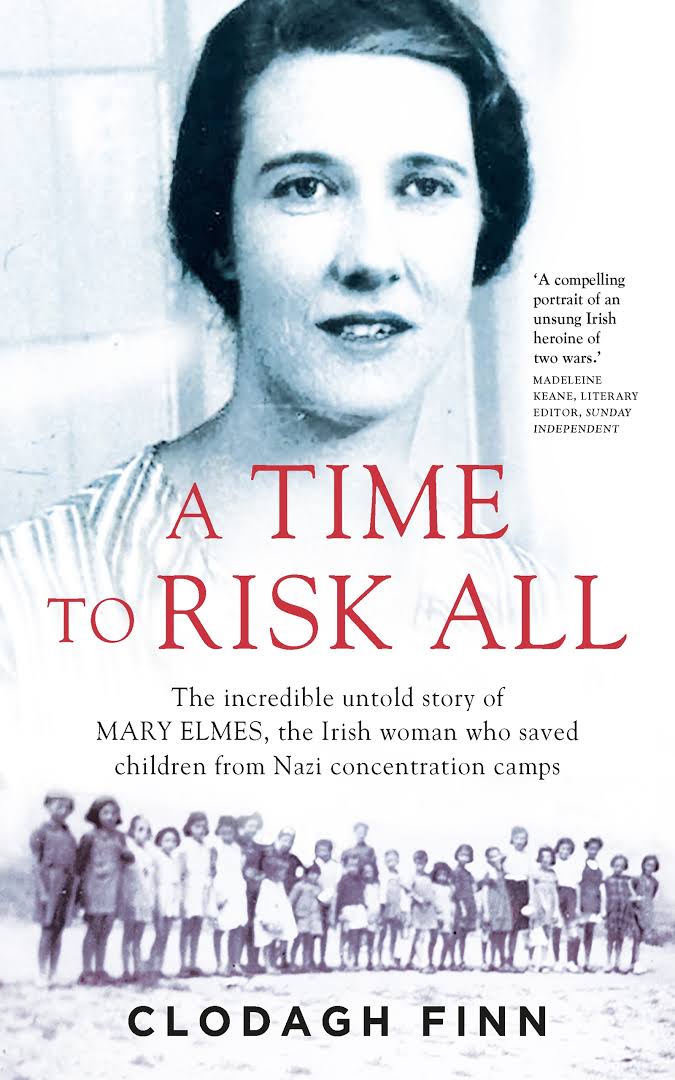

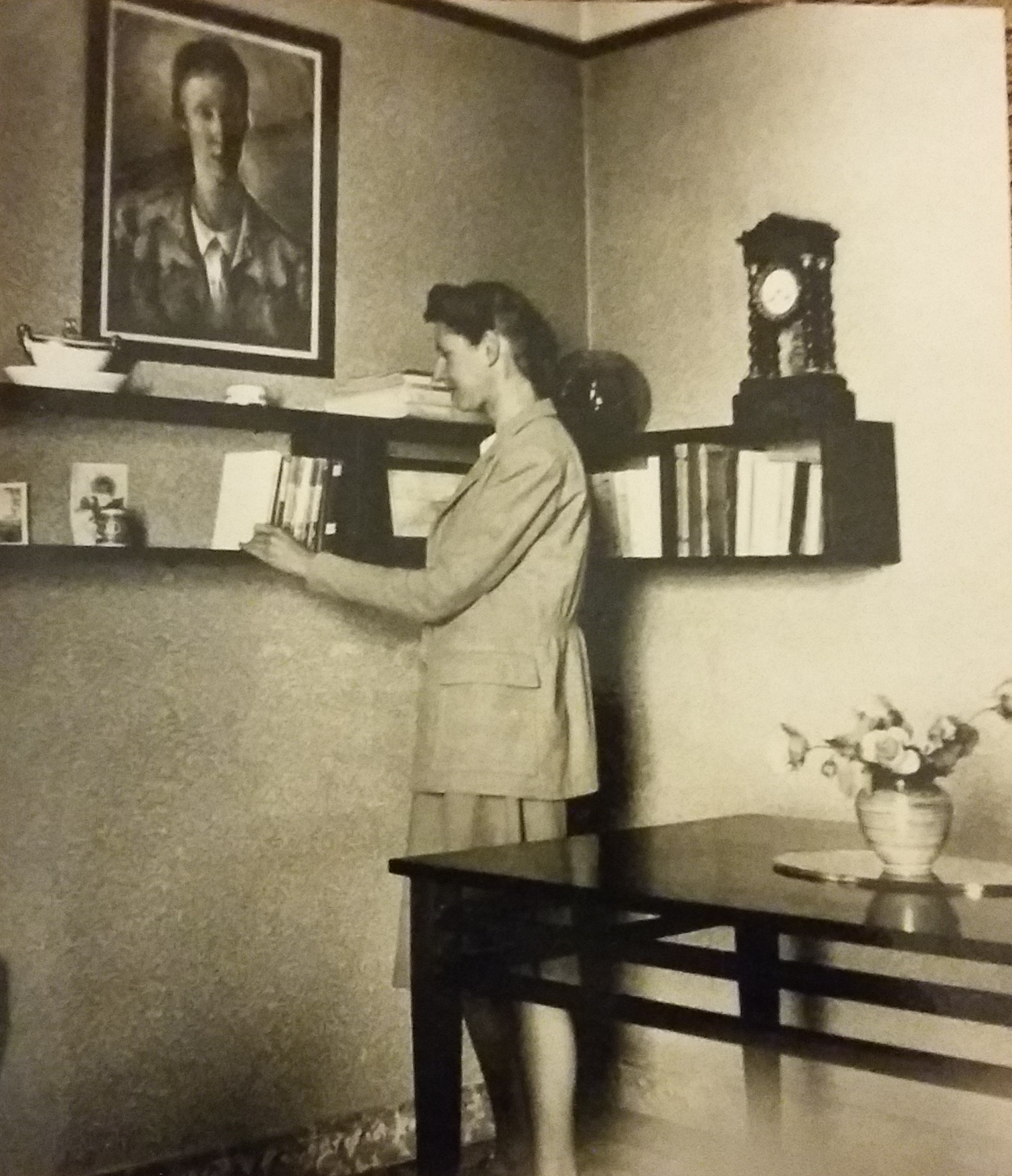

MARY ELMES / ‘The Irish Oskar Schindler’

MARY ELMES

Scholar, linguist and heroine of two wars

‘The Irish Oskar Schindler’

MARY Elmes, a Corkwoman and Trinity scholar, turned her back on a brilliant academic career to volunteer in two of the 20th century’s worst conflicts. During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), she set up and ran children’s hospitals, moving from site to site as Franco’s troops advanced. When it was no longer safe to stay, she followed the Spanish refugees over the border into France and found herself in another war – World War II. She continued to help refugees and later risked her life to save Jewish children from deportation.

In a sense, Marie Elisabeth Jean Elmes experienced the turbulence of war from a very young age. She was born on 5 May 1908 into a prosperous – and progressive – home in Ballintemple, Cork city. Her father Edward Elmes was a pharmacist and her mother Elisabeth Elmes campaigned for the vote for women as treasurer of the Munster Women’s Franchise League.

Mary (as she was later called) and her younger brother John both attended La Rochelle, a modern and well-equipped school in Blackrock, Cork. The school imposed a “rigid curtain of censorship” in an attempt to keep the political upheaval of the early 20th century out, but without success.

A very young Mary was aware of World War I and, aged seven, knitted socks for soldiers fighting on the front line. The war came much closer to home in May 1915 when the Cunard ocean liner the Lusitania was torpedoed by a German U-boat off the coast of Cork. She and her family joined the thousands who flocked to Cobh to help the survivors. She would tell her children that the heartrending scenes she saw on the quayside that day stayed with her for life.

She also had reason to remember the Irish War of Independence. In 1920, the family business on Winthrop Street was burned out by British forces. Despite the turmoil, Mary Elmes was encouraged to travel and to study. When she finished school, she spent a year in France and came home with near-perfect French. She went on to study Modern Languages (French and Spanish) at Trinity College Dublin where she excelled. In 1931, she won a Gold Medal for academic excellence and, after graduating, a scholarship to the London School of Economics (LSE).

A former professor at Trinity, T.B. Rudmose-Brown, enthused about her “unusual intelligence” and her “exceptionally brilliant academic career”. In London, the accolades continued to come. In 1936, she won another scholarship, this time to study international relations in Geneva.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in the same year, Mary would have been keenly aware of the political background but nothing could have prepared her for the suffering she witnessed when she volunteered to join Sir George Young’s University Ambulance Unit. She arrived in Spain in February 1937 and was assigned to a feeding station in Almeria.

She soon gained a reputation as a shrewd and able administrator who was clear-headed and unsentimental in the chaos of war. As the fascist army advanced, Mary moved eastwards, from Murcia to Alicante and then into the mountains at Polop, setting up and running children’s hospitals as she went. When her father died unexpectedly in Cork at the end of 1937, she missed the funeral because she refused to abandon her post when a replacement couldn’t be found.

She left Spain only when it became impossible for aid workers to stay and then she followed her beloved Spanish refugees over the border into France. Using the skills she had acquired, Mary set up workshops, canteens, schools and hospitals in the hastily erected camp-villages in southwest France.

‘I liked to make people do things,’ she explained many years later during a rare interview. ‘But I didn’t just give orders. I did things myself. I got things done. I had a fixed point of view and I went on with it. I was not emotional but rather clinical, like a doctor, or a soldier, I suppose. Luckily, I became hardened. It allowed me to work constantly.’

She was single-minded in her work as head of the Quaker delegation in Perpignan. Hundreds of her surviving letters reveal a determined and resourceful woman, but also a very diplomatic one.

Those traits would prove vital when Jews in southwest France were rounded up to be deported from Rivesaltes camp where Mary Elmes spent most of her time.

Surviving documents describe how she ‘spirited away’ nine Jewish children from the first convoy bound for Auschwitz on 11 August 1942. She bundled them into the boot of her car and drove them to the children’s homes she had set up in the foothills of the Pyrenees and along the coast earlier in the war.

Between August and October 1942, Mary Elmes and her colleagues saved an estimated 427 children from Rivesaltes camp.

Her efforts brought her to the attention of the Gestapo and in early 1943 she was arrested and jailed for six months. When asked about it afterwards, she simply said: “Well, we all experienced inconveniences in those days, didn't we?”

When the war was over, she married Frenchman Roger Danjou in Perpignan and they had two children, Caroline and Patrick. She spoke little of the war or what she had done, refusing all accolades in her lifetime.

In 2011, nine years after her death at the age 93, one of the children she saved, Professor Ronald Friend, nominated her for Israel’s highest award; two years later she was named Righteous Among the Nations. She is the only Irish person to hold the honour, which is given to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during World War II.

Picture courtesy of Caroline and Patrick Danjou, Mary Elmes’s children.

Herstory from Clodagh Finn, author of Mary Elmes’s biography, 'A Time to Risk All' published by Gill Books, €16.99.

https://www.gillbooks.ie/biography/biography/a-time-to-risk-all

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Time-Risk-All-Clodagh-Finn/dp/0717175618

CONSTANCE WILDE (HOLLAND) / Campaigner for suffrage & rational dress

CONSTANCE WILDE (HOLLAND)

Campaigner for suffrage and rational dress, and wife of Oscar Wilde

London

1859 – 1898

In Oscar Wilde: a Summing Up, Lord Alfred Douglas, the love of Wilde’s later life, wrote about Wilde’s marriage to Constance Lloyd. He characterised it as ‘a marriage of deep love and affection on both sides’. Oscar described Constance as ‘quite young, very grave, and mystical, with wonderful eyes, and dark brown coils of hair’. His mother thought her: ‘A very nice pretty sensible girl-well-connected and well brought up’. Yet Constance, who had a troubled adolescence, could appear shy and lacking in confidence.

A recent upsurge in interest – exemplified by Franny Moyle’s excellent biography Constance: the Tragic and Scandalous Life of Mrs Oscar Wilde and my own Wilde’s Women - reveals a bright, progressive and politically active woman who was as loyal and true to her errant husband as her name suggests. Newspaper accounts of the time pay tribute to her beauty but also cover her campaigns for the greater participation of women in public life, and praise her aptitude as a public speaker.

Constance spoke excellent French and Italian. She was also a remarkable accomplished pianist. Her strong views on dress reform led her to join the committee of the Rational Dress Society in order to campaign for an end to the ridiculous, restrictive fashions that prevented women from leading fulfilling lives. In ‘Clothed in Our Right Minds’, a lecture she addressed to the Rational Dress Society in 1888, she advocated the wearing of divided skirts, insisting that, as God had given women two legs, they should have the freedom to use them. She broadened her argument to suggest that women deserved a wider role in all aspects of life.

A member of the Chelsea Women’s Liberal Association, Constance campaigned to have Lady Margaret Sandhurst elected to the London County Council. Addressing a conference sponsored by the Women’s Committee of the International Arbitration and Peace Association on the theme ‘By what methods can Women Best Promote the Cause of International Concorde’; she stressed the importance of encouraging pacifist ideals at an early age and insisted: ‘Children should be taught in their nursery to be against war’. Her speech ‘Home Rule for Ireland’, delivered at the Women’s Liberal Federation annual conference of 1889 was praised in the Pall Mall Gazette.

Yet, Constance’s world fell apart when her husband was arrested and imprisoned for gross indecency. Obliged to flee abroad with her young children and to change her family name to Holland, she did everything she could to help Oscar. Tentative attempts to effect reconciliation were brought to an end when she died as a result of a botched operation performed in an Italian clinic in April 1898. She was thirty-nine years old. Regrettably, Constance is often portrayed as a figure of pity. In reality, she was strong and courageous, warm and true, and she met the many challenges she faced, including debilitating health problems, with steely determination.

Thanks to herstorian Eleanor Fitzsimons for this herstory.

Sources:

Eleanor Fitzsimons. Wilde's Women. (London: Duckworth, 2015)

Franny Moyle. Constance: The Tragic and Scandalous Life of Mrs Oscar Wilde (London: John Murray, 2012)