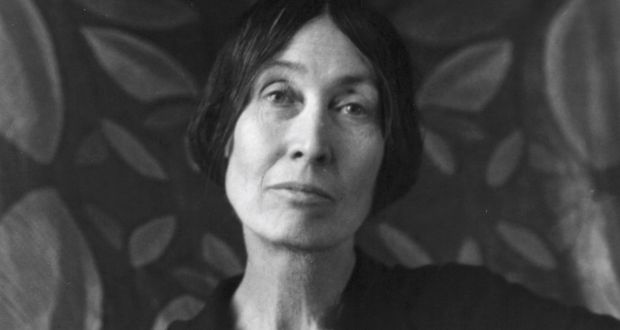

1863-1946

… I gladly testify to the wholehearted and devoted service of Miss Agnes Gallagher and her two sisters […] from 1915 onwards. They organised concerts, carried out National Aid work, assisted in organising activities and at a later stage rendered the greatest service to the West Mayo flying column through the provision of clothing and supplies, the maintenance of communications and supplying information. […] Miss Gallagher’s enthusiasm, devotion and unselfishness were always a fountain of inspiration and encouragement for the young men and women of the Westport district. The moral support given to us at all times by herself and her family was of the greatest value and must be reckoned with the financial aid and the practical assistance which they gave in a wide range of cultural, and political, as well as military, activities over a long period of years. Miss Gallagher’s services in the national movement cannot be sufficiently appreciated by those who had not personal knowledge of her work and of the intimate relations of trust which existed between her family and the local Volunteer and IRA organisations.’

-Thomas Derrig (Commandent of the West Mayo Brigade of the Irish Volunteers)

Early Life

Agnes Gallagher was born on 19 November 1863 in Westport, Mayo to Patrick Gallagher and Margaret Gill. She was the sixth of ten children born to the couple and had a further two older half siblings through her father. One of these, Martin Gallagher was a ‘conspicuous figure in Irish national affairs’ as a fenian and had to flee the country for America in the late 1860s after being labelled a ‘marked man’, when Agnes was still a small child. (i) Likewise, the Gill branch of her family tree were highly active in seeking Ireland’s independence. Her first cousin Major John MacBride would end up as one of the leaders shot in 1916 and his brother Joseph would be elected to represent south Mayo in 1918.

The Gallagher family were quite well-off and both Agnes and her sister Kathleen were trained instrumental musicians on the violin. By 1880 Agnes was playing at local concerts.

Involvement in the Gaelic Revival

Both Agnes and her sister are recorded as ‘music teachers’ in the 1901 census. It is understood that the women taught from home, in what Agnes called an ‘academy’, with young female students attending their house for lessons.

In 1904 Agnes was on the instrumental music judging panel at the Mayo Feis which ran for three days and proved that the Gaelic movement had taken ‘great hold’ in the West (i). The feis promoted Irish singing, dancing and story-telling, as well as Irish crafts and agriculture. President of the Gaelic League (and later, the first president of Ireland) Douglas Hyde was also in attendance representing the League, as well as Patrick Pearse and Agnes O’Farrelly, who would be one of the founding members of Cumann na mBan in 1914.

Early Activity

In 1915, at the age of fifty-two, Agnes helped to found the Mayo branch of Cumann na mBan. Little is known of her early activities but on 24 April 1916 (Easter Monday), she organised a concert to help raise funds for the Volunteers.

She organised concerts frequently in order to raise money for both the Volunteers and Fianna Eireann, as she had an orchestra of her own, of twenty-four people whom she taught. She stated in her pension application file that during this particular concert they heard of ‘this thing in Dublin’ and that all the artists were then taken away and the police arrived. (ii) In the months that followed, Agnes would on occasion hire artists from Dublin to come to Mayo to play at these concerts in order to draw in a bigger crowd, and she would pay them out of her own pocket.

Agnes was also involved in organising financial support for dependents of volunteers in prison, as well as anti-recruiting against British Forces.

In September 1917 she was sent as a delegate to Thomas Ashe’s funeral in Dublin. Ashe had been a member of the IRB, Gaelic League and a founding member of the Irish Volunteers. Upon being arrested and refused ‘prisoner of war’ status, he went on hunger strike and died after being force fed. 30,000 attended the procession to Glasnevin cemetery where Michael Collins gave a eulogy. The event is seen by many as a turning point in the attitudes of the Irish public towards the ideal of an Irish Republic.

In 1918, while continuing her fund raising, Agnes campaigned heavily for the election of her cousin Joseph MacBride as Sinn Fein MP for the Mayo West constituency. No doubt she spearheaded a lot of his campaign for him, as he was imprisoned at the time, having been arrested in May of that year. She herself referred to it as an ‘intensive canvas’ and stated that by that time, she was organising concerts to take place every Sunday. (ii) The two cousins appear to have been very close, as Agnes even acted as his seconder when it came to candidate nominations in early December 1918.

Sinn Fein won 73 out of 105 possible Irish seats, Joseph taking one of them, by mid-December. Just one month later, on 21 January 1919, Sinn Fein MP’s refused to recognise the UK Parliament and instead established a revolutionary parliament they named Dail Eireann in the Mansion House, Dublin, on the exact same day that the Irish War of Independence began.

War of Independence (1919-1921)

From April of that year, Agnes began to provide accommodation for the Courts of Dail Eireann, which was declared illegal by the British in September 1919. Her house on Bridge Street, Westport had already been established as a meeting place for the IRB before Easter Week 1916, so it was no surprise that she hosted the likes of Arthur Griffith, Thomas Derrig and Michael Kilroy during the War of Independence. She also canvassed for, and collected, subscriptions for the Internal loan of the Dail Eireann at this time.

Between 1919 and 1920, searches were constantly being carried out on Agnes’ young female students to the extent that her Academy had to be closed because ‘the children were afraid to come in.’ (ii) The British forces also conducted many raids on her house, one in particular was in search of a gun they believed to be hidden there. In fact, a Thompson machine gun was in the house at the time, but Agnes managed to conceal it well enough that it was never found. On another occasion, she got word that her house was to be burned out, so she cleared the building of almost all the furniture. The house was saved when the Black and Tans ran out of petrol a few doors down from her home.

Of these raids, Agnes said:

…They would come in the middle of the night too and raid us. Nothing but r…. and raids. That was the Tan time. They wanted to take over our house from us. The Auxiliaries came and demanded the house.

Sometime in autumn 1920, ‘strangers’ to the locality came to Agnes’ front door. They were Tans ‘with revolvers in their hands’ and they ‘inquired for Miss Agnes Gallagher.’ (ii) In order to evade arrest, she was forced to leave her house and go on the run. She went to Islandmore and Clew Bay and ‘organised the girls’ there. She trained them to conduct scouting work ‘to see when the boats were coming.’ (ii)

Returning to her house by Christmas, Agnes and her two sisters, Nora and Kathleen, set up a communication station and received despatches from Newport and Louisburg and from other surrounding areas. Rarely trusting anyone else to deliver the messages to the boys, Agnes often went herself, two or three times a week.

On 19 May 1921, six IRA men were killed and seven wounded in what is now known as the Kilmeena Ambush. In her pension application, Agnes states that she forwarded information she got regarding the attack on Kilmeena, which turned out to be correct. Her information would have been vital, for it has been said that ‘it was a crucial week in the survival of the column because they were attacked from the rear at Kilmeena and could have been wiped out during this action.’ (iii)

Truce period

On 11 July 1921, a truce was called. From 12 July, Agnes began to give her house up again for conferences and billeting of senior officers of the IRA. It was also used as a liaison office to debate over the terms of the Truce being offered. This must have been a very difficult time for Agnes, who remained fiercely anti-Treaty and republican, as among everything else, her close ally and cousin, Joseph MacBride, went pro-Treaty. Of the split in their party, Agnes said ‘I could not prevent them. I did my best to keep them back.’ (ii) In spite of the turmoil in her own home, Agnes continued to raise funds for the IRA and actively campaigned for them during the Truce period with her grand-niece Eileen Dineen (daughter of Francis Dineen, fourth president of the GAA) who she seemed to have raised with her sisters.

Civil War (1922-1923)

On 28 June 1922, civil war broke out. The anti-Treaty Irish Republicans were on one side, and the pro-Treaty Irish nationalists on the other. About this time, Agnes began to procure rifles and ammunition for the IRA. She did this by having another person negotiate with Free State forces over the Barracks walls. These men were selling boots, clothes and ammunition which Agnes took advantage of through her negotiator. She got about eight or nine rifles this way and then would leave them in a prearranged place for the IRA to pick up, or else transport them through the bread van. She also purchased leggings and other small items from a shopkeeper in Westport who had refused to sell the stuff to the IRA members. They did however, sell it to Agnes, who was forced to pay the bills accumulated herself.

On two occasions, Agnes traveled to Dublin for Cumann na mBan related business. She attended a meeting at 6 Harcourt Street where she liaised with Nancy ‘Nannie’ O’Rahilly and Mrs Mary Kate O’Kelly (successful academic in her own right and first wife of Sean T. O’Kelly, second President of Ireland). She had planned the trips in order to get more equipment for the IRA in her locality, but as they didn’t have enough for themselves in Dublin, she failed to attain anything of any use.

Agnes helped to re-organise an Intelligence service in Westport around this time in order to forward warnings of impending attacks to the local boys. This was done through a network of Cumann na mBan women stationed in different parts of the surrounding areas, as well as information obtained from Free State soldiers or their friends. In late October, her house was fired on by Free State troops, she being nearly shot herself. Of the terrifying experience, she had the following to say:

They shot a very valuable dog on us. The house was raided three times that night. We never went to bed. It was the night they were coming back from the raid on Clifden. They expected the boys would be coming back from there and kept raiding all night.

On 22 November 1922, Agnes got word of an ambush organised for the next day in north Mayo, where she knew Michael Kilroy and his column where. She said that she got this information from a friend of hers, Joseph Ruddy, who she had known from her time in the Sinn Fein club, and who was now a captain in the national forces. He had visited her that morning and of the visit she said:

… they were getting ready in the barracks, for a raid. I sent them word there was a detachment going down. I could infer they were going from what he said.

Agnes went personally to give this information to Michael Kilroy. Of the night she said:

I was walking – you could not cycle on the road; it was patrolled. One would be held up. They had outposts everywhere. It was about nine o clock at night. I had to go across the fields – I dare not go on the road. I passed the outpost, and they followed me. I got in under the railway bridge, and they kept firing but did not know where I was. I knew all the cross-cuts and I got out on the Newport road. I got a girl out there to go down with the dispatch to Kilroy. I knew there was a Brigade meeting on. They were surrounded the next morning.

Michael Kilroy was wounded and captured the next day. Agnes’ friend, Joseph Ruddy, was killed.

Prison Time and Hunger Strikes

On 21 April 1923, at fifty-nine years old, Agnes was arrested by Claremorris troops and sent to Galway prison without trial. Her arrest was not unusual in the area, where it was reported in March of that year that ‘it is almost an every-day sight to see prisoners being marched by a strong military guard to the station on the way to internment.’ (iv) Upon arrival she was described as a 5ft 5 3/4in woman with grey hair, blue eyes and fresh complexion.

On 21 May she was transferred to Kilmainham jail in Dublin, and despite the Civil War coming to an end three days later on 24 May, Agnes remained incarcerated. Here, she would have lived in poor conditions. One Minnie Lenihan, a Galway girl who spent time in Kilmainham, said that thirty women were expected to live in a dormitory no bigger than 30 by 20 feet. (v) During her time here, Agnes went on two hunger strikes, one which resulted in her losing her sight. After striking for ten days in one instance, Agnes said:

…we were pretty weak and were not able to go out in the air for recreation, and we opened one of the windows to get fresh air. There was a soldier in the Crows Nest, and he always shot at the prisoners when he saw them at the windows. I did not know this. They shouted to me that he was going to fire. I stumbled back and fell, and broke two ribs, and my eye came against the table with the result I was never able to teach music since I came home or take up any position.

Even with the injuries she sustained, Agnes was not released from prison. Instead, on 28 September she was transferred again, this time to North Dublin Union. One woman described the NDU as follows:

… the condition of the place was filthy beyond description, the treatment was worse, the diet was worse, and altogether, in every respect, it was the worst period of [her] confinement.

On 13 October, with no release in sight and under worsening conditions in the prisons, a mass hunger strike was announced by Michael Kilroy. Within days, there were over 7,000 Republicans in prisons around the country on hunger strike, and fifty of those were women in the North Dublin Union, including Agnes.

Later Life

Eventually, on 27 October 1923, Agnes was released from prison and sent back to Mayo. At almost sixty years old, and suffering from spending four months in terrible conditions in prison, during which time she underwent three separate hunger strikes, Agnes’ health was very poor. Now blind, Agnes was unable to resume her music teaching and could not take up a new position. She was primarily supported financially by her brother Edward. In September 1934 she began the process of applying for a military pension, but it wasn’t until 1942 that she would finally be granted one of Grade E status, £17 10s per annum. She appealed the decision as she felt that she deserved a higher grade than one of the lowest possible, however, her appeal was denied. One of those who wrote her a reference in her favour, was cousin, Joseph MacBride.

Agnes died at her home on 19 June 1946, after a ten-day illness, at the age of 82.

Herstory by Katelyn Hanna.

Sources:

(i) Connaught Telegraph, 3 Aug. 1901.

(ii) Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), MSP34REF3344: Agnes Gallagher, online at Military Archives, http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/detail.aspx?parentpriref= (accessed 20 Mar. 2018).

(iii) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Kilroy

(iv) Connacht Tribune, 10 Mar. 1923.

(v) Connacht Tribune, 15 Sept. 1923.